Notes on AI-Driven Development: Rewriting Polyscope in Rust

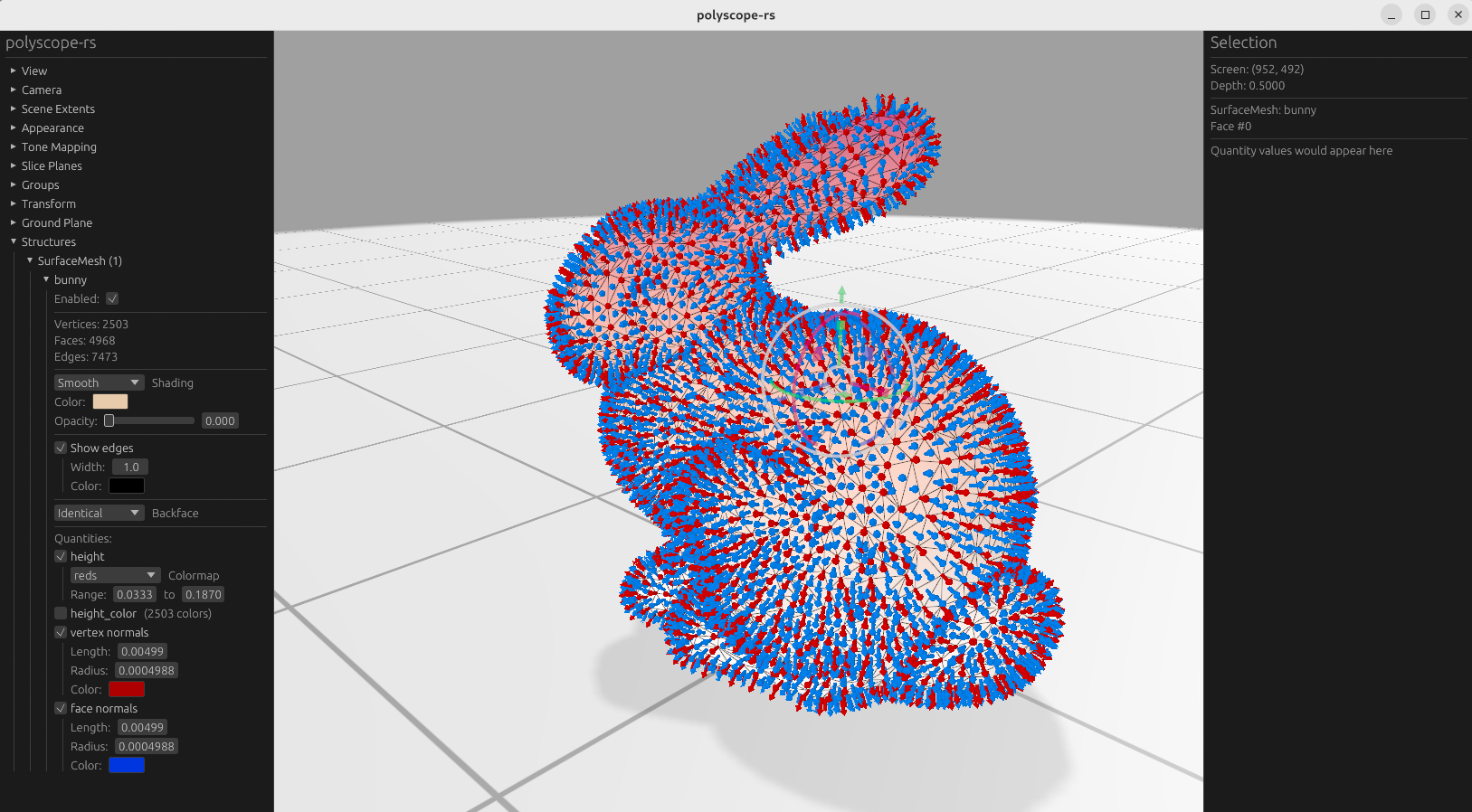

This post documents my experience rewriting Polyscope, a C++ 3D visualization library, in Rust using Claude Opus 4.5 as the primary development tool. The resulting project, polyscope-rs, has reached 100% feature parity with the original C++ implementation. This was accomplished over around 2 weeks of spare time, working on it intermittently.

I am NOT a Rust developer by background—my experience is primarily in C++, Python, and C#. However, I have used Polyscope in several research projects and have contributed to the original repository, so I understand its architecture. This combination—unfamiliar implementation language, familiar problem domain—made for an interesting test case.

The hypothesis motivating this experiment was straightforward: programming languages with stronger compiler feedback and better tooling should be more suitable for AI-assisted development.

The following differences between Rust and C++ proved particularly relevant for AI-assisted development:

| Aspect | Rust | C++ |

|---|---|---|

| Compiler errors | Precise, actionable messages with suggested fixes | Template errors are notoriously verbose and difficult to parse |

| Package management | Unified (Cargo handles dependencies, building, testing) | Fragmented (CMake, Conan, vcpkg, Bazel, manual management) |

| Standard tooling | Built-in formatter (rustfmt), linter (clippy), documentation (cargo doc) | Multiple competing tools with inconsistent adoption |

| Error handling | Explicit via Result<T, E> and Option<T> types | Implicit (exceptions, error codes, undefined behavior) |

| Language consistency | Single modern paradigm with limited legacy | Decades of accumulated features with multiple ways to do the same thing |

When an AI generates incorrect code (which happens frequently), these tooling and language design differences determine how efficiently corrections can be made. The more structured and explicit the feedback, the faster the iteration cycle.

A secondary motivation was to test whether domain expertise could compensate for lack of language expertise when working with AI tools.

Through trial and error over around 2 weeks, I converged on the following practices:

Structured workflow. After comparing the two currently famous plugins for Claude Code, everything-claude-code (Claude hackathon winner) and superpower, I chose the latter for its strict and systematic procedure for the software development cycle: brainstorming - planning - implementation.

Description-based debugging. For debugging, I found it effective to describe observed behavior and let the agent figure it out: "The mesh renders correctly but vertex colors appear inverted." The agent could typically identify and correct issues within one or two iterations using this approach.

Model capability. Claude Opus 4.5 is, to my knowledge, the most capable model currently available for this type of work. It still produces errors regularly, even with careful prompting. These are typically not obvious mistakes but subtle misinterpretations—applying a pattern from one context inappropriately to another, or optimizing for the wrong constraint. Continuous review remains necessary. The agent also tends to accumulate rather than refactor code; periodic manual cleanup cycles are required to maintain code quality and prevent architectural drift.

Context limitations. Long development sessions degraded in quality. As the context window filled with compilation output and debugging history, the model began losing track of earlier results, prompts, and constraints specified in reference documents like CLAUDE.md. (One useful trick: adding a line in the reference file instructing the model to prefix responses with a specific phrase—e.g., "Sir, yes sir"—makes it immediately obvious when the model has stopped reading the file.) Running implementation tasks in separate, focused sessions—while maintaining a primary session for coordination—produced better results.

Domain knowledge. This proved essential. The agent could implement code within an architectural framework but could not design the architecture itself. Since the Rust ecosystem lacks direct equivalents for several libraries used in the original C++ Polyscope (and the rendering systems differ—OpenGL vs. wgpu), critical decisions needed to be made based on domain expertise. This requirement becomes even more significant when designing systems from scratch, where the agent can provide suggestions but cannot make definitive architectural choices. As AI-assisted programming becomes more prevalent, developers will need to develop stronger skills in architectural decision-making and requirement specification.

Compiler as collaborator. The Rust compiler served as an effective first-pass reviewer. The feedback loop—agent generates code, compiler catches type errors, agent reads error message and corrects—worked remarkably well. This would not have been possible with C++'s less informative error messages.

Token consumption. Development in Rust consumed more tokens than equivalent Python projects I have worked on, but fewer than comparable C++ projects. The compile-debug cycle generates substantial output that enters the context window, which should be considered when planning development budgets.

Extended debugging sessions. Two debugging sessions exceeded 30 minutes, both involving rendering problems deep in the render engine and pipeline. These problems were particularly challenging because the rendering system involves many interconnected components—materials, lighting, ambient shadows, and multiple geometry types (curves, surface meshes, volume meshes, point clouds). The tight coupling made it difficult to isolate issues, even for a human familiar with the system. What was notable was the agent's persistence: it would continuously reconsider strategies, add debugging code, implement tracing mechanisms, run tests, observe results, and iteratively narrow down the problem. The agents demonstrated a methodical approach to debugging that would be tedious but necessary for humans. In one case, the first fix attempt was incorrect, but after I provided additional context based on my domain knowledge, the agent successfully resolved the issue in the second round. These sessions suggested that for sufficiently complex debugging tasks, the agent's ability to execute systematic investigation processes can be valuable, even when architectural guidance remains necessary.

This project changed how I think about programming. AI-driven development isn't about automation replacing human work—it's about fundamentally changing what that work consists of. I spent far less time writing code and far more time specifying requirements, reviewing output, and making architectural decisions. These are different skills than traditional programming requires.

The developer's role is shifting upward in abstraction. I'm increasingly responsible for architecture and specification rather than implementation. My domain expertise became more valuable for evaluating correctness—not just whether code compiles, but whether it solves the right problem correctly. Meanwhile, I'll inevitably understand fewer implementation details as AI writes most of the code. This inversion is uncomfortable but seems fundamental to the new model.

Code organization matters differently now. I initially accumulated a 4,000-line engine.rs file along the AI-driven coding process, which caused recurring bugs more and more often as the project size increased. The agents couldn't parse the entire file in one pass and instead used grep to glimpse fragments, missing important context. After refactoring into several ~1,000-line files, code quality improved significantly. Traditional metrics like "minimize file count" or "colocate related functionality" need to be balanced against "keep files small enough for the model to hold in context." As the project grows more complex, token consumption escalates—each new feature or bug investigation requires more context for the agent to understand the system. Modularized design helps with this issue by isolating concerns, but the fundamental problem persists: complexity accumulates faster than context windows expand.

Language design matters more than I expected. Not just for developer ergonomics, but for how well an AI can work within the feedback loops. Rust's compiler acted as a tireless first-pass reviewer, and the unified tooling (Cargo) eliminated entire categories of configuration problems that would have consumed context window space in C++. In AI-assisted development, language quality directly multiplies productivity in ways that weren't as apparent when humans wrote all the code.

These are lessons from a single project, and I expect best practices to evolve rapidly as both models and tooling improve. But the core insight feels durable: in AI-assisted development, the human's job is increasingly about architecture and specification rather than implementation.

The polyscope-rs source code is available at github.com/xarthurx/polyscope-rs.